What It Means to 'Be a Contemplative'

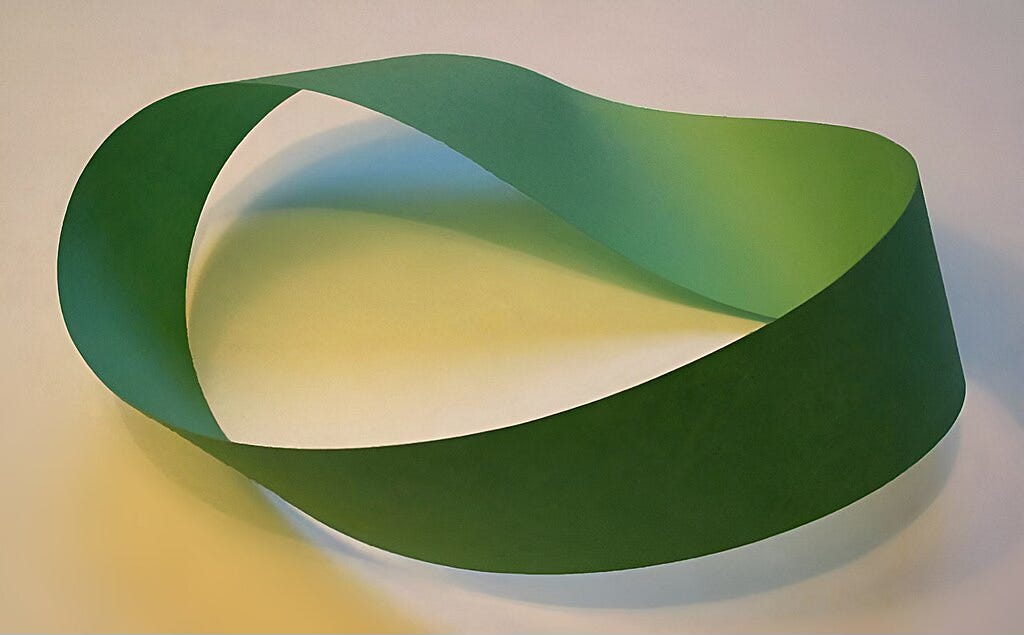

Exploring the Möbius strip of contemplation and action.

For so many years, I longed to be a contemplative. I saw it as a kind of state or identity—an ideal way of being that I yearned to embody. I immersed myself in the writings of Thomas Merton and the anonymous author of The Cloud of Unknowing. Even during my years in academia, I noticed how the early mornings carried a different essence—quiet, alive, fertile.

That was the time I felt most inspired, when my writing and meditations would flow freely. I ached to live more fully in that rhythm, much like the monks and sages who retreated into hermitages.

During the pandemic, in my small 800-square-foot Philadelphia apartment that I called my hermitage, I cloistered myself from the noise of the world. I lived simply, venturing out only occasionally, then returning to my hot cocoa and my contemplative books. That quiet life suited me.

The ‘Stages’ in The Cloud of Unknowing

If you’re not familiar with The Cloud of Unknowing, it is a 14th century text written by a monk to a younger monk. Although people may describe it as an instruction manual, it’s not. In fact, the first time you encounter it may invite more questions than answers. That’s why it’s important to read it several times throughout your life, if you have the patience.

What can be misleading about The Cloud of Unknowing is that it sets up a dichotomy between the active and contemplative life. There also seems to be a hierarchy, referring to “lower” and “higher.” There’s a “lower active” that may include people’s involvement with church activities—a more outer-facing religious life. Or it’s an idea that God is “out there.” The author considers Martha of Bethany as an example.

Then there’s the “higher active” who may consider a bit of inward dwelling of God while serving others. The “lower contemplatives” may prefer to immerse themselves with contemplative, introspective practices. The author says that many people may move between “higher active” and “lower contemplative” as they are members of society.

The author then considers Mary of Bethany to be the model of the “higher contemplative” who prefers to sit at the feet of Jesus rather than be “worried and distracted by many things.” Because Jesus tells Martha that this is “better” (the author uses the word “best,” but that’s for another time), I yearned to live a life like Mary of Bethany. I was a contemplative wannabe.

Yet even then, something felt unmoving—like tending a garden that refused to bloom.

The Night of the Senses

I then remembered what John of the Cross calls the night of the senses: that period when spirituality feels barren and unresponsive, as though God has withdrawn. Beneath it, though, is a deeper pruning—the stripping away of self-attachment. Depression often accompanied it, whispering old refrains of not being enough, of losing hope. For years, I lived in that shadowed terrain—half longing for the divine, half bound by despair.

Even though The Cloud of Unknowing and St. John of the Cross’s Dark Night of the Soul are considered to be contemplative texts, I couldn’t really reconcile the two. How does the dark night of the senses fit in with these various stages of contemplation? In other words, if I was a “lower contemplative,” what does that fit within the spiritual aridity described by St. John of the Cross?

I realized that defining yourself in various stages, assessing yourself (or someone else assessing you), and asserting this idea of yourself in society is just a ploy of your ego. All these definitions, roles, and Enneagram numbers serve as limitations. They may help to make some sense of this moment, but this moment quickly passes away. In other words, you must “unknow” yourself, your identities, and your concept of God. That’s really what The Cloud of Unknowing is getting at.

Beyond Stages and States

Parker Palmer’s image of the inner and outer life as a Möbius strip feels more fitting—two sides of the same surface, seamlessly flowing into one another. Our inner, authentic self and our outer active self are not separate realms but complementary aspects of one life. One is the creative energy, and the other is the creative expression.

The contemplative life is not a title to claim—it’s an ever-present invitation that unfolds within the ordinary. We all have a “higher contemplative” self that yearns to animate our lives.

The Inner Castle

St. Teresa of Ávila offers a vision that feels especially relevant to the modern seeker: the soul as an interior castle with many rooms, each one leading closer to the divine center. Contemplation, in this view, is not an identity or achievement but a homecoming—a turning inward toward the God who already dwells within.

Thomas Merton, too, underwent this realization. In his later writings, he corrected his early notion of contemplation as separate from action. He wrote:

True contemplation is inseparable from life and from the dynamism of life, which includes work, creation, production, fruitfulness, and above all, love. It is not a separate department of life, but the fullness of a fully integrated life—the crown of life and all life’s activities.1

“Being a contemplative” is not a withdrawal from the world but recognizing the fullness within it.

Finding the Why in God

Years ago, Simon Sinek popularized the idea of “Finding Your Why.” It’s a helpful lens for the spiritual journey, too. The contemplative path, at its core, is about finding your Why, who is God. Our actions—teaching, serving, creating—may begin with good intentions, but often they are still entangled with our need for success, belonging, or recognition. The “dark night” arrives when those illusions are stripped away, leaving only the pure desire for God.

As St. Augustine wrote, “Our hearts are restless until they rest in Thee.” The contemplative path is the process of clearing away everything that keeps us from that rest. It’s about remembering our deepest Why—again and again—and letting it guide both our inward stillness and our outward service.

Integration: The Dance of Inner and Outer

Merton wrote that the contemplative “seeks to know the meaning of life not only with his head, but with his whole being… by living it in depth and purity.”2 Contemplation, he said, is related to art, to worship, to charity—each reaching beyond the material into transcendent meaning. Through this, “they transfigure the whole of life.”3

That, to me, is the essence of the contemplative path. It is not about achieving a state or wearing a label. It is about living in such a way that God animates our every breath and movement—where love becomes the current that moves through all we do.

Letting God Animate the Clay

In the end, being a contemplative is not about mastering stillness or perfecting devotion. It is about taking our hands off the wheel and letting God drive. It’s letting God shape our lives like clay on the potter’s wheel—reforming, remolding, and expressing through us.

We act not from ego but from grace.

We speak not from striving but from surrender.

We live not to attain God, but to allow God to live through us.

And that is the heart of contemplation: the merging of stillness and action, silence and song, the inward and the outward, until there is no longer a separation—only love flowing in both directions.

From A Thomas Merton Reader, edited by Thomas P. McDonnell, p. 400.

Ibid., p. 401

Ibid., p. 402.